With 1923 nearly over, I’m running out of time to share more of the thoughts and ideas I found regarding Australian literature in 1923 from Trove. This post, I thought to share some of the ideas expressed about humour in Australian literature.

Humour wasn’t always specifically mentioned in 1923 as being a feature of Australian literature, but was mentioned enough to suggest that some, at least, appreciated its use.

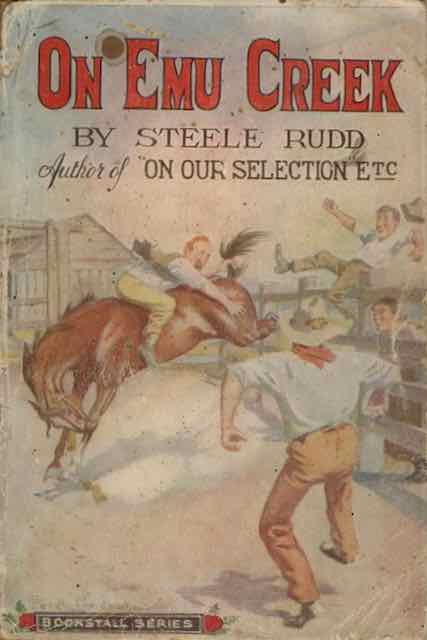

The most frequent mention I found concerned, Steele Rudd, famous for the Dad and Dave stories. He is praised for using humour to make interesting and enjoyable the truths he has to tell about Australian lives. The Queensland Times (2 May) introduced Rudd’s new book, On Emu Creek, and describes it as giving “full play to his whimsical humour, his knowledge of the rural dwellers, and his sympathy with their struggles”. Melbourne’s The Age (5 May) is more measured, but seems also to like the humour, describing it as “an agreeable story, without any affectation of style, and containing points of humor”.

Others, though, are a little less enamoured, with various reviewers qualifying their approval. One of these is J.Penn, writing in Adelaide’s The Register (19 May). There is some satire, he says,

But the main idea of nearly every chapter is someone being knocked over. It is difficult to think of any other humourist who would not seek to find humorous terms in which to describe intendedly humorous incidents. But Steele Rudd is firmly convinced that his readers will find sufficient fun in the mere fact of some one being humiliated or hurt, without the author’s having to worry to hunt for words.

Ouch … This is not to say that J.Penn doesn’t like humour. He clearly likes satire. And, he critiques another 1923 literary endeavour for lacking “gaiety”. It was a literary magazine titled Vision: A Literary Quarterly, that was edited by Frank C Johnson (comic book and pulp magazine publisher), Jack Lindsay (writer and son of Norman Lindsay), and Kenneth Slessor (poet). The quarterly, which only lasted 4 issues, aimed, says AustLit, “to usher in an Australian renaissance to bolster the literary and artistic traditions rejected by European modernists”, but they also wanted to “invigorate an Australian culture they claimed was stifled by the regressive provincialism of publications such as the Bulletin“.

Anti-modernist in ethos, Vision, continues AustLit, was influenced by “Norman Lindsay’s principles of beauty, passion, youth, vitality, sexuality and courage” and “consistently provided readers with potentially offensive content”. Penn was thoughtful about the first issue:

It is a welcome guest, as giving outlet for a lot of good work which might not find a fair chance elsewhere. But it has three faults, one of outlook, two of detail. Contemplation of sex matters is not the only way to brighten life; yet they constitute quite four-fifths of this opening number.

Not only that, but, he says, ‘while it would seem difficult to be heavy, even “stodgy,” on matters of sex, that feat has been accomplished here’. Indeed, it has “no spark of gaiety”, which is exactly what Norman Lindsay, in the same issue, accuses James Joyce of. (Excuse the prepositional ending!) However, not all of Vision is like this:

The poetry in this volume, by Kenneth Slessor and others, has much of the desired element of gaiety; and a page of brief quotations from modern writers in other countries, with satirical footnotes, is delightful. There remain the pictures. These are as bright and gay as could be wished—a riot of triumphant nudity, in which Norman Lindsay in particular finds full opportunity.

Overall, he feels that “with some judicious editing, this endeavour to brighten Australia should have at any rate an artistic success”. (Also, he does like Jack Lindsay’s “valuable essay … on Australian poetry and nationalism, with a theory that we must get away from shearers and horses”.)

A very different magazine is one praised for its cheerfulness, Aussie. It ran from 1918 to 1931, and had various subtitles, The Cheerful Monthly, The National Monthly, and The Australian Soldiers’ Magazine. I had not heard of it before, but AustLit once again came to my rescue. Created for soldiers in Europe, most of its early contents came from them, and comprised, says AustLit, “jokes, anecdotes, poems and drawings” which reflected “the character (most likely censored) of the Australian soldier in World War One”. In 1920, it was revived as a civilian magazine, but “the humour … was maintained”. Now, though, its contributors were established writers and artists, like AG Stephens, Myra Morris, and Roderic Quinn. I found a review of a 1923 issue in The Armidale Chronicle (19 September). It is unfailingly positive, telling its readers that “every page of Aussie breathes cheerfulness, and there is not a joke, a picture, or a story that fails to portray some phase of Australasian humor”. I wish it described what it meant by “Australasian humor” but the word it uses most is “cheerfulness”. This perhaps makes sense, given AustLit’s assessment that “it maintained its position between political extremes, addressing the views of a predominantly middle-class audience”.

Humour is also mentioned reviews of books for children, such as The sunshine family, by Ethel Turner and her daughter Jean Curlewis. It is described in the Newcastle Morning Herald and Miners’ Advocate (14 December) as having “rare good humour”, but is that unusual for a book for children?

The descriptions of the 100 books chosen by AG Stevens for Canada, that I wrote about earlier this year, include several references to humour – in fiction, such as EG Dyson’s 1906 Factory ‘ands, with its “brilliant satirical humour”; in children’s books, like C Lloyd’s 1921 The house of just fancy, whose pictures “have quaint loving humour”; and in much of the poetry, including JP Bourke’s 1915 Off the bluebush, which contains “verses of sardonic humour”.

Humour is such a tricky thing – from the sort of situational humour in Rudd’s On Emu Creek, through the apparent “cheerfulness” of Aussie, to the more satirical humour liked by J.Penn – but unfortunately, most of the references I found don’t analyse it in much detail. I will keep an eye out as we go through the years.

Meanwhile, do you like humour in your reading? And if so, what do you like most?

Other posts in the series: 1. Bookstall Co (update); 2. Platypus Series; 3 & 4. Austra-Zealand’s best books and Canada (1) and (2); 5. Novels and their subjects; 6. A postal controversy