A week or so ago, I saw a post by Cathy (746 Books) that she was taking part in a Doorstoppers in December reading event. My first thought was that December is the last month I would commit to reading doorstoppers. In fact, my reading group agrees that doorstopper month is January, our Southern Hemisphere summer holiday month. That’s the only month we willingly schedule a long book. My second thought was that I call these books “big baggy monsters”. But, that’s not complimentary I know – and I do like many big books. Also, it’s not alliterative, which is almost de rigueur for these blog reading challenges.

Anyhow, I will not be taking active part, but it seemed like a good opportunity for a Monday Musings. I’ll start with definitions because, of course, definition is an essential component of any challenge. The challenge has been initiated by Laura Tisdall, so she has defined the term for the participants. (Although, readers are an anarchic lot and can also make up their own rules! We wouldn’t have it any other way, would we?) Here is what she says:

Genre conventions vary so much. For litfic, for example, which tends to run shorter, I can see anything over 350 pages qualifying as a doorstopper, whereas in epic fantasy, 400 pages would probably be bog standard. Let’s say it has to at least hit the 350-page mark – and we encourage taking on those real 500-page or 600-page + behemoths

I love her recognition that what is a doorstopper isn’t absolute, that it does depend on the conventions or expectations of different forms or genres. I will focus on the literary fiction end of the spectrum but I think 350 pages is a bit short, particularly if I want to narrow the field a bit, so I’m going to set my target for this post at 450 pages. I am also going to limit my selected list to fiction published this century (albeit the challenge, itself, is not limited to fiction.)

However, I will commence with a little nod to doorstoppers our past. The nineteenth century was the century of big baggy monsters, even in Australia. And “baggy” is the right word for some, due partly to the fact that many were initially published in newspapers as serials, so they tended to, let me say, ramble a bit to keep people interested over the long haul. Dickens is the obvious example of a writer of big digressive books.

In 19th century Australia, publishing was just getting going so the pickings are fewer, but there’s Marcus Clarke’s 1874 His natural life (later For the term of his natural life). Pagination varies widely with edition, but let’s average it to 500pp. Catherine Martin’s 1890 An Australian girl is around 470pp. Rolf Boldrewood’s Robbery under arms runs between 400 and 450pp in most editions, while Caroline Leakey’s 1859 The broad arrow is shorter, with editions averaging around 400pp.

By the 20th century, Australian publishing was growing. Like Leakey’s novel, Joseph Furphy/Tom Collins’ 1903 Such is life is shorter, averaging 400pp (Bill’s final post). Henry Handel Richardson’s 1930 The fortunes of Richard Mahony, depending on the edition, comes in around the 950pp mark. Of course, it was initially published as three separate, and therefore relatively short, volumes but the doorstopper edition is the one I first knew in my family home. Throughout the century many doorstoppers hit the bookstands, including books by Christina Stead in the 1930s and 40s, Xavier Herbert from the 1930s to the 1970s (when his doorstopper extraordinaire, Poor fellow my country was published), Patrick White from the 1950s to late in his career, and on to writers like Pater Carey whose second novel, 1985’s Illywhacker, was 600 pages. He went on to publish more big novels through the late 20th and into the 21st century.

Selected 21st Century Doorstoppers

The list below draws from novels I’ve read from this century. In cases where I’ve read more than one doorstopper from that author, I’ve just chosen one.

- Peter Carey, Parrot and Olivier in America (2009, 464pp, my review)

- Trent Dalton, Boy swallows universe (2018, 474pp, my review)

- Michelle de Kretser, Questions of travel (2012, 517pp, my review)

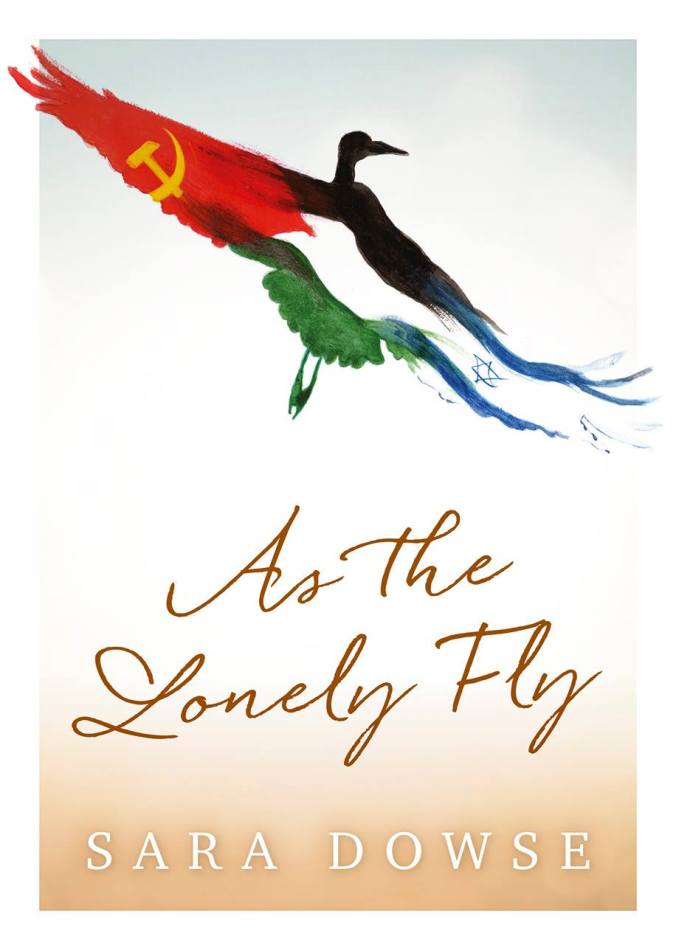

- Sara Dowse, As the lonely fly (2017, 480pp, my review)

- Richard Flanagan, The narrow road to the deep north (2013, 466pp, my review)

- Elliot Perlman, The street sweeper (2011, 626pp, my review)

- Wendy Scarfe, Hunger town (2014, 456pp, my review)

- Steve Toltz, A fraction of a whole (2008, 561pp, my review)

- Christos Tsiolkas, The slap (2008, 485pp, my review)

- Tim Winton, Dirt music (2001, 465pp, read before blogging)

- Alexis Wright, Carpentaria (2006, 526pp, my review)

There are many more but this is a start. They include historical and contemporary fiction. Many offer grand sweeps, while some, like Scarfe’s Hunger town, are tightly focused. The grand sweep – mostly across and/or place – is of course not unusual in doorstoppers. A few are comic or satiric in tone, like Carey’s Parrot and Olivier in America, while others are serious, and sometimes quite dark. The authors include First Nations Alexis Wright and some of migrant background. And, male writers outweigh the females. Perhaps it’s in proportion to the male-female publication ratio? I don’t have the statistics to prove or disprove this. Most of these authors have written many books, not all of which are big, meaning the form has followed the function!

Are you planning to take part in Doorstoppers in December? And, if you are, what are you planning to read? Regardless, how do doorstoppers fit into your reading practice?