In last week’s 1962-themed Monday Musings post, I mentioned that I would post separately on the Dame Mary Gilmore Award. This was because it has an interesting history.

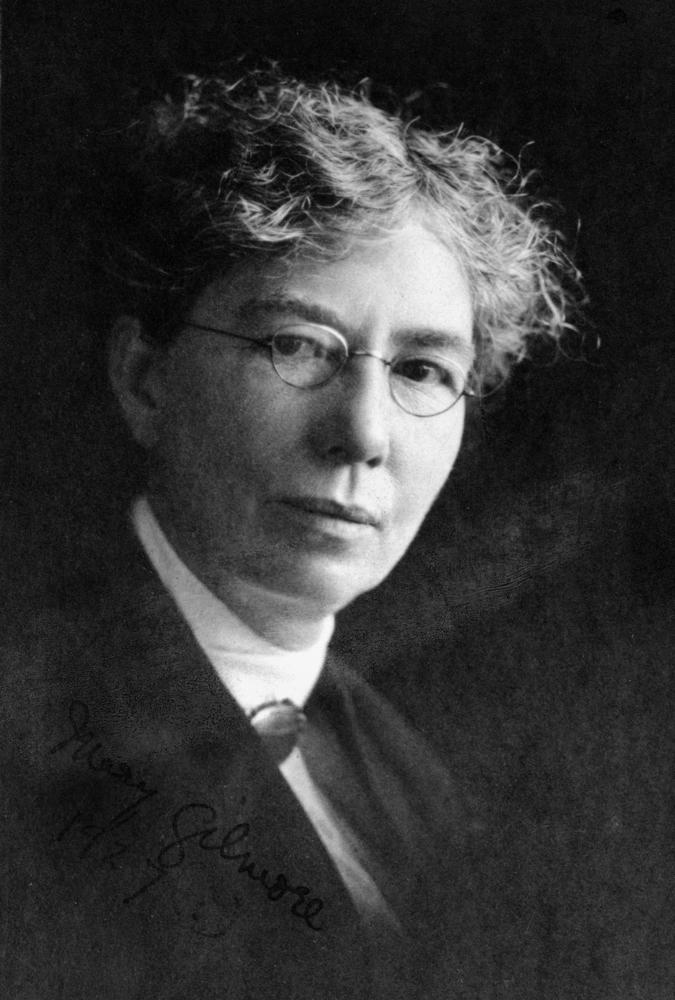

First though, a bit on Mary Gilmore, for those who don’t know here. She was an Australian writer and journalist, best known as a poet. One day, I will write separately on her, but for now, I will just say that she was highly political, and was part of the utopian socialist New Australia colony set up by William Lane in Paraguay. I wrote about this in another Monday Musings back in 2015.

Gilmore lived a long life, dying in 1962 (in fact!), at the age of 97. She was involved in socialist and trade union movements, and wrote for Tribune, the Communist Party of Australia’s newspaper, though she was apparently never a party member. Her political interests are relevant to the award.

The Award has been known by different names since its creation in 1956 by the ACTU, the Australian Council of Trade Unions. According to AustLit, it was called the ACTU Dame Mary Gilmore Award, and its goal was, ‘to encourage literature “significant to the life and aspirations of the Australian People”‘. Over the years, says Wikipedia, it has been “awarded for a range of categories, including novels, poetry, a three-act (full-length) play, and a short story”. Reading between the lines, I assume this means it was more about content than form.

Since 1985, it has been confined to poetry – to a first book of poetry, in fact – and since around 2019 has been managed by ASAL, the Association for the Study of Australian Literature. Its specific history, I must say, is not particularly clear, but at some time its name was simplified to the Mary Gilmore Award. It was awarded annually until 1998, was then biennial until 2016, but now seems to be annual again. It’s a good example of the challenge to survive that many awards face. The Wikipedia article linked above lists the winners from 1985 to the present.

Pre-1985

It’s the early years of the award that I’m most interested in, mainly because they are less well documented. I’ve tried various search permutations in Trove and have found scattered bits of information, some of which I’ll share here. My first comment is, Wot’s in a name?

I have not found a formal announcement of the award, unless this advertisement in the Tribune of 21 March 1956, the year the award was apparently established, is it. It calls the award the Mary Gilmore Prize, and says submissions should be made to the Victorian May Day Committee. The May Day Committee isn’t the ACTU, but they are closely related, and both support workers’ rights. Indeed, the Victorian May Day Committee page notes that “The labour movement and the trade union movement should continue to build this day as it is the working people’s day”.

Anyhow, the ad invites submissions to the “May Day competitions” and then says that “the best three stories and the best three verses will be eligible for consideration for the Mary Gilmore Prize of £50”. It sounds like May Day literary competitions were already established – the prizes were small, just £5 and £3 – but now a bigger prize was to be offered in the name of Mary Gilmore. And, this year at least, short stories and poetry were the chosen forms. The ad also says that:

The short story and verse most favored by the judges will be those best expressing the aspirations and democratic traditions of the Australian people.

Then, on 12 December 1956, the Tribune announced that “two Mary Gilmore Literary Competitions have been announced by the May Day Committees of Melbourne; Sydney, Brisbane and Newcastle”. For May Day 1957, the “Mary Gilmore Literary Competition” would award prizes for the “first and second short stories and poems, in each of two classes”, meaning four prizes in each class. Class A was for “established” (or )published writers, and B for “new” writers. For May Day 1958, they offered the “Mary Gilmore Novel Competition”, with “a substantial prize, to be announced later” for the “best novel submitted”. The overall announcement added that:

The judges will prefer stories and poems which deal with the life and aspirations of the Australian people.

You can see how tricky the history of awards can be. I have to assume this is the “ACTU Dame Mary Gilmore Award”.

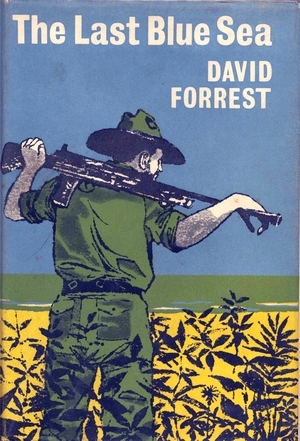

The next mention I found – and I could have missed some – was from the Tribune of 6 January 1960, which, announcing some new publications from the Australasian Book Society, included

Available now, The last blue sea – David Forrest (Winner, Dame Mary Gilmore Award).

Interestingly, it’s a World War II set story.

Then, again in the Tribune, but this one, almost two years later on 13 December 1961, there is a report on a reception for Ron Tullipan who had won “the 1961 Dame Mary Gilmore Award for his novel, Rear vision“. It’s quite an extensive report which includes references to Jack Beasley, who was “one of the judges of the competition, which is sponsored each year in association with May Day celebrations”. He was concerned about the suggested takeover of the publisher, Angus and Robertson, by Consolidated Press. Read the article if you are interested. The report also noted that:

The Dame Mary Gilmore Award was probably unique in the capitalist world, and a real contribution to Australian literature.

On 22 August 1962, the Tribune announced the presentation of the Dame Mary Gilmore Awards for “poetry, novels and stories”. The winners were Jack Penberthy’s story, “The Bridge”, and Dennis Kevans’ poem, “For Rebecca”. Mysteriously, no novel is named. This report also helpfully names past winners of the award, but without more detail – Joan Hendry, Vera Deacon, Ron Tullipan, Dorothy Hewett, Hugh Mason, and David Forrest. Dorothy Hewett is probably the only one of these still known today.

This article also shared that the Award’s National Chairman, George Seelaf, believed that “in a few years they would be the major literary competitions in our country” but “still more financial support from more unions” was “urgently required”:

“Trade Unionism has always been strongest and literature has always been strongest when writers and unions were closest together. We will encourage writers who tell of the life and aspirations of the Australian people”.

Don’t you love this conviction about the value of literature?

Also in 1962, another Tribune article (5 September), quotes the Dame herself. She didn’t attend the presentation, but the paper reports

that she was particularly glad to learn of the high standard and the large number of entries. “The more writers, the better expressed will be the thoughts and wishes of Australians,” she says.

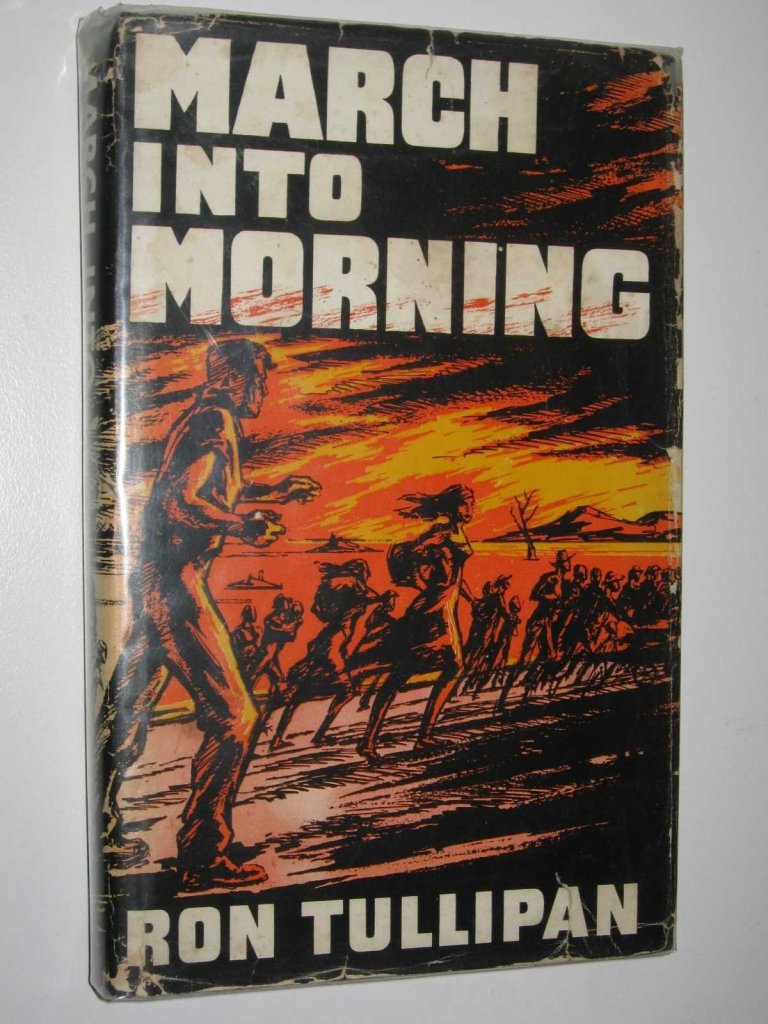

The Canberra Times – for a change – reported on 29 September 1962 that Ron Tullipan had won the “Mary Gilmore Award” with his “hard novel”, March into morning (which I described in my last Monday Musings). Is this the novel not mentioned in Tribune’s August report?

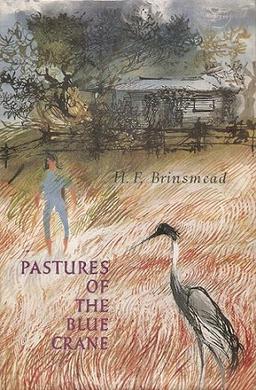

I found more award-winners from the 1960s, and they are interesting in terms of form. In 1963, for example, Hesba Brinsmead’s manuscript of the children’s (young adult) book, Pastures of the blue crane, won. That year, the “Mary Gilmore Award” was for a children’s book, with a second award for a book by a teenager. (Tribune 16 January 1963). In 1967, Pat Flower won the “Dame Mary Gilmore Award” for her hour-long television drama, Tilley landed on our shores. By then, the award was worth $500.

More work needs to be done on this, but it looks like the Dame Mary Gilmore Award Committee would decide each year what the award was for, rather than make it always open to multiple forms. The 1964 award, for example, seems to have been for a novel, while the 1966 one was for poetry. Whatever, the point is that all through this era of the award, the trade unions were behind it, until – well, I haven’t discovered yet how that aspect of it ended. But, what an interesting award.

Thoughts?