Of all the writers I’ve researched for the AWW project, Beatrice Grimshaw is among the most documented, with articles in the Australian Dictionary of Biography (ADB) and Wikipedia, among others. And yet, she is little known today. This post, like most of my recent Forgotten Writers posts, draws on the one I posted on AWW. However, I have abbreviated that post somewhat here to add more commentary.

If you are interested, check out the story I shared on AWW, a romance titled “Shadow of the palm”. It provides a good sense of what she wrote – and why it might have value today, despite its problematic language. It tells of local traditions and lustful dissolute men, of missionaries and young people in love. It is a predictable story typical of its time, but is enlivened by knowledge of a place that was exotic to its readers. It also conveys some of the cultural conflict and exploitation that came with colonialism.

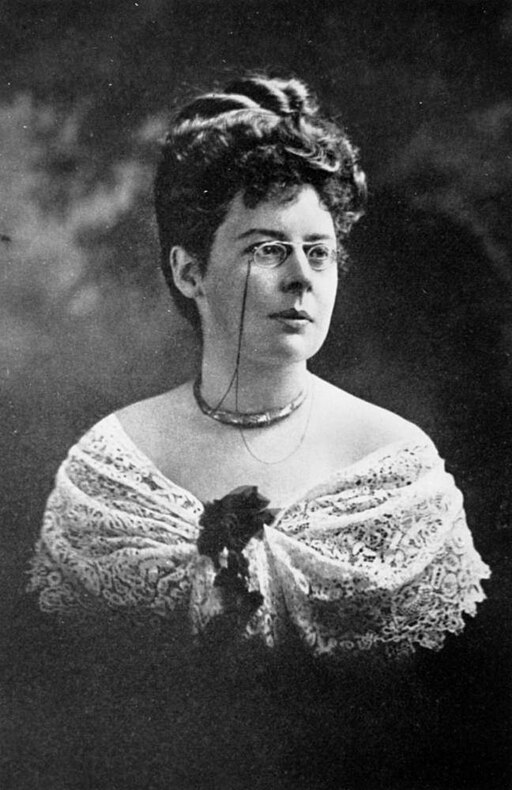

Beatrice Grimshaw

Beatrice Ethel Grimshaw (1870-1953) is described by Wikipedia as “an Irish writer and traveller”, while the ADB does not give a nationality. However, both state that she was born on 3 February 1870 at Cloona, Antrim, in Ireland, and died on 30 June 1953 at Kelso near Bathurst in New South Wales. She is buried in Bathurst cemetery.

Grimshaw, the fourth of six children, was never going to be the little wife and mother. Wikipedia says that she “defied her parents’ expectations to marry or become a teacher, instead working for various shipping companies” while ADB says that, although she went to university, “she did not take a degree and never married but saw herself as a liberated ‘New Woman'”. There is much detail about her life at these two sources so I’ll just share the salient points here. She loved the outdoors, and began her writing career when she became a sports journalist for Irish Cyclist magazine in 1891. Besides working as an editor, she wrote “a range of content including poems, dialogues, short stories, and two serialised novels under a pen name”. Her first novel, Broken away, was published in 1897.

“a fearless character” (HJB)

The early details aren’t fully clear, but from some time after 1891, she worked for various shipping companies in the Canary Islands, the USA and England. Things become clear by 1903 when we know she left for the Pacific to report on the region for the Daily Graphic. She also accepted government and other commissions to write tourist publicity for various Pacific islands and NZ.

In 1907, she returned to Papua, intending to stay for two or three months, having been being commissioned by the London Times and the Sydney Morning Herald as a travel writer, but ended up living there for most of the next twenty-seven years. She wrote, joined expeditions up rivers and into the jungles, managed a plantation (1917-22), and established a short-lived tobacco plantation with her brother (1934). She played a key role in the development of tourism in the South Pacific.

Due to recurring malaria fever, she moved to Kelso in 1936 to live with her brothers. She didn’t retire, however. She continued to write books, and undertake other work, including, according to Broken Hill’s Barrier Daily Truth (12 Feb 1943) “liaison work for the Americans in Australia … She said that Australia offers unlimited opportunities for expansion, opportunities which the American people will be quick to utilise”.

Grimshaw was a prolific and best-selling writer, with over 35 novels to her name. She drew from her experiences in the South Seas, and wrote in the popular genres of the time – romantic adventure, crime fiction and some supernatural or ghost stories. The Armidale Express and New England General Advertiser (3 July 1940) reported that many of her novels and short stories had been “translated into German, French, Danish and Swedish” and that her books were “known throughout England, America and Australia”. She also wrote numerous articles and short stories for papers and journals. Her 1922 novel, Conn of the Coral Seas, was made into a film, The Adorable Outcast, in 1928.

She was quite the celebrity, for her adventurous life as well as for her writing. After all, as The Australian Women’s Weekly (Feb 1935) pointed out, she had lived amongst “headhunters”, no less! Her writing was frequently praised for its realism, with a reviewer in Adelaide’s The Register writing (9 Sept 1922) identifying “two outstanding features of her writing” as:

her understanding of human nature, and her power of description. There is no need to illustrate her books. Her own words conjure up pictures as accurate as they are enchanting …

Some though were more measured, like the writer in The Queenslander (4 Mar 1922) who admired her storytelling but was “forced to wonder if the beautiful islands hold nothing but hatred and dark intrigue”. That though, was surely her genre more than the truth speaking!

Nonetheless, for modern readers her writing is problematic. We can’t, as Byrne writes, overlook “her paternalistic and occasionally racist attitudes” in her fiction and her journalistic writing. Take her reference to Japanese divers as “little yellow men” (The Australian Women’s Weekly 1940) or this much earlier one on Papuans:

The native is willing to work—unlike the Pacific Islander—and a good fellow when well treated. His interests are being thoughtfully cared for, and he is governed with honesty and justice. (Sydney Morning Herald, 14 December 1907)

And yet, if you read this SMH article, you will gain an impression of the liveliness of her observations, which brings me to why she is worth reading. Her writing is a valuable historical source. She wrote a lot, in depth, and with excellent powers of observation about the Pacific, and in doing so conveys information about the life of European settlers, along with the values, beliefs, and attitudes they had. It has to be gold for anyone researching that time and place.

AustLit notes that she was, in her day, “sometimes favourably compared with Joseph Conrad, Bret Harte and Robert Louis Stevenson”, but that she is out of print today. More interestingly, the Oxford Companion shares that researcher Susan Gardner concluded that she “was made up of contradictions” including that “between her explicit anti-feminism and her feminist career”. A most fascinating, forgotten woman.

Sources

HJB, “At home with Beatrice Grimshaw, Novelist”, Sydney Mail (9 December 1931) [Accessed: 10 February 2026]

Angela Bryne, “Beatrice Grimshaw: The Belfast explorer treated as a male chief on Samoa“, The Irish Times (5 March 2019) [Accessed: 2 March 2026]

Beatrice Grimshaw, AustLit (Accessed: 8 February 2026]

Beatrice Grimshaw, Wikipedia [Accessed: 7 February 2026]

Hugh Laracy, ‘Grimshaw, Beatrice Ethel (1870–1953)‘, Australian Dictionary of Biography, Australian National University, 1983 [Accessed: 7 February 2026]

William H. Wilde, Joy Hooton and Barry Andrews, The Oxford companion to Australian literature. Melbourne, Oxford University Press, 2nd, edition, 1994

All other sources are linked in the article.