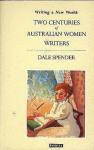

Last year I wrote a series of posts about 1922, drawing primarily from Trove. I enjoyed doing it, and have decided to repeat the exercise this year, and perhaps continue annually, to build up a picture of the times. My first 1922 post was about the NSW Bookstall Company which was established in 1880, but which around 1904 began publishing and selling Australian books for one shilling each. When I started my 1923 Trove search, this company featured heavily, so I’ve decided to lead off with an update of it.

Now, I noted last year, that the company’s longstanding managing director, A.C. Rowlandson, had died that year, but that the company planned to continue. During this year’s research, I found that in 2000 the University of Melbourne’s Baillieu Library put on an exhibition titled “Sensational Tales: Australian Popular Publishing 1850s-1990s”. One of the “tales” concerned the NSW Bookstall Co. They confirmed that the Company had “helped make writing a viable occupation for a generation of Australians, a number of whom – including Norman Lindsay, Vance Palmer and ‘Steele Rudd’ – achieved lasting reputations”. However, they also say that the Company’s publishing program did decline after Rowlandson’s death, and that it issued fewer than 70 titles between 1924 and 1946. By the end of World War II, the Company had “reverted to being a retail distributor of books and magazines”. How much of this decline was due to Rowlandson’s death and how much to changing times, they don’t say, but, from what I’ve read of him, I suspect the former played a role, as Rowlandson was clearly a powerful and inspirational force.

Anyhow, on with 1923. I plan to share the fiction that I’ve identified as published by them in 1923. What is interesting is not just who the Australian authors were and what they were writing, but what the reviewers and commentators were saying about both the company and the specific books, and what it all reveals about Australia’s literary environment of the time.

Bookstall Series books, 1923

Although the University of Melbourne’s exhibition notes the company’s decline, it was still going strong in 1923:

- Vera Baker, The mystery outlaw (pub. 1920, and 1923)

- Capel Boake, The Romany mark

- Dale Collins, Stolen or strayed

- Arthur Crocker, The great Turon mystery

- A.R. Falk, The red star

- J.D. Fitzgerald, Children of the sunlight: stories of Australian circus life

- Jack McLaren, Fagaloa’s daughter

- Jack North, A son of the bush

- Ernest Osborne, The plantation manager

- Steele Rudd, On Emu Creek

- Charles E. Sayers, The jumping double: a racing story

- H.F. Wickham, The Great Western Road

Most of these authors are male. Indeed, Capel Boake and Vera Baker seem to be the only woman here.

I found several references for most of the books listed above. Some were not much more than listings, and some seemed to be somewhat repetitive (which could be due to syndication and/or drawing from publisher’s publicity. It’s hard to know without deeper analysis.) However, there was also some more extensive commentary.

First though, as you can probably tell from the titles, the books tend to be “commercial” or genre books, most of them adventure with some mystery thrown in. One of my 1922 posts focused on the time’s interest in adventure, so I won’t repeat much of that except to say that many of the reviewers/columnists talked about “thrills”, “exciting reading”, fast pacing, and the like. The majority of the novels are set in the bush, reflecting our well-documented ongoing interest in outback stories. But A.R. Falk’s detective novel The red star, is set in Sydney. The Brisbane Courier’s reviewer (23 June) argues that Australian writers hadn’t “developed the field of detective fiction to any extent”, which is interesting given its popularity now. This reviewer praises the book saying that Falk had “written a far better detective story than the majority of those that are imported”. S/he says that “the fight between detectives and a clever gang of thieves and murderers is told in a very convincing manner” and that while “the ending, perhaps, is forced” the story “takes a high place among current detective fiction”.

That’s higher praise than some of the books received at the hands of our reviewers. J.Penn tended to write a little more analytically. I haven’t been able to identify who J.Penn is, but s/he wrote a new books column in Adelaide’s Observer and Register titled “The Library Table”. S/he generally praised Ernest Osborne’s The plantation manager but did note a weakness at times for ‘making people “talk like a book”‘ (Observer, 5 May) and was critical of Steele Rudd’s On Emu Creek which s/he felt lacked the satirical edge of his Dad works. S/he writes that “Steele Rudd is firmly convinced that his readers will find sufficient fun in the mere fact of some one being humiliated or hurt, without the author’s having to worry to hunt for words” (Register, 19 May). The Murray Pioneer and Australian River Record (3 August) described On Emu Creek as humorous but qualified this with “the reader may be pardoned if he fails to see in the more recent books the same rich vein of humor that characterised the earlier chronicles of the Rudd family” while The Age (5 May) was gentler, calling it “an agreeable story, without any affectation of style, and containing points of humor”

Penn described (Register, 21 April) Dale Collins’ Stolen or strayed as ‘a “shilling shocker” of modern Australia’. Set mostly on the Murray, “it is,” writes Penn “a joyous yarn, and, as generally happens nowadays, the literary style is more than worthy of the tale it unfolds”. Interestingly, though, Collins’ book generated more disagreement than most. The Queenslander (12 May) was less impressed, saying that “neither the workmanship nor the characterisation show any especial ability” and The Sun (22 April) said that “It is a story just good enough, so far as construction is concerned, to lead one to hope that the author will do much better some day.”

Overall, several reviewers commented along the lines of Perth’s Western Mail (26 April) reviewer, who said, regarding Stolen or strayed and The planation manager, that “both books will no doubt be read with avidity by those who care for stories of this kind”. This is fair enough given these readers were Bookstall’s target market.

Now, some quick observations, before closing. I was interested that some reviewers seemed to give the whole plot away, which we don’t see now. Also, I’ve not (yet) been able to identify several of the authors, but a few were also journalists – like Dale Collins and Jack North – and some used pseudonyms, like Capel Boake about whom I’ve written before.

Finally, despite what seemed to be qualified praise for many of the books, it’s clear that the endeavour was valued for providing a career for Australian writers and illustrators at a time when they struggled to get published. And, as Hobart’s Mercury (18 August) wrote

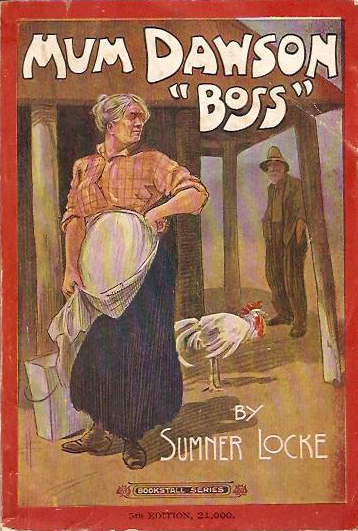

Beyond question, they are more than worth the money, the thing most prejudicial to their success being the gaudy “Deadwood Dick” types of covers in which they appear.

Trove (et al) under threat

You all know how much I rely on Trove. Back in 2016 I wrote a post in support of it when its survival was threatened. Well, it’s under threat again, and Lisa posted on it today. She references an(other) article in The Conversation that addresses not only the situation for the National Library of Australia and Trove, but other significant national cultural institutions like the National Film and Sound Archive and the National Gallery of Australia. These services and institutions are the lifeblood of academics, writers, journalists and other researchers (professional and general). Their role is to acquire, preserve and make available our heritage. They are not dispensable. They are essential.