During 1925, two sets of articles appeared which discussed the issue of fostering “Australian sentiment”.

Australian literature and labour

Herald (Melbourne), 27 November 1929, p 16

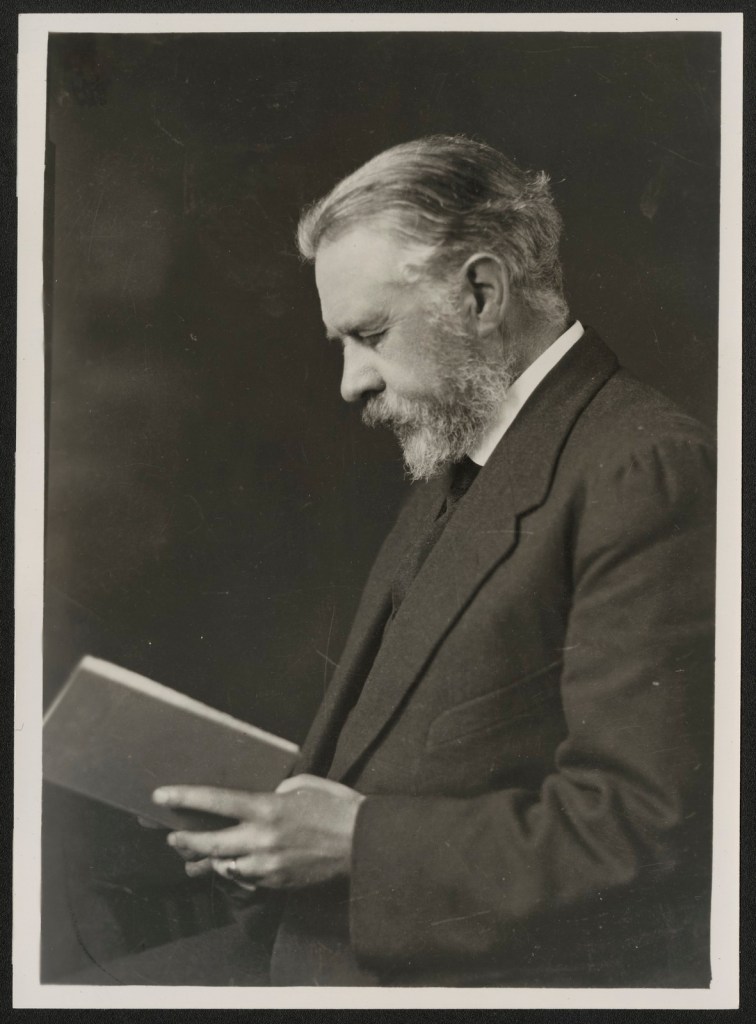

During the year, John McKellar (1881-1966) gave lectures on topics relating to literature and labour or the working class. On February 12, a newspaper titled Labor Call advised that at the February 17 meeting of the Malvern Branch of the ALP, Mr McKellar would speak on “Literature: Its relation to working class progress.” I didn’t know John McKellar but he has an entry in the ANU’s Labour Australia site. He was an “engineer, trade union official, editor and author”. He unsuccessfully stood for Labor in both state and federal elections and was associated with the Jindyworobak movement which focused on promoting Australian culture. He published books of essays, and historical articles, including one on a Gippsland-based Christian Socialist commune. His political and cultural interests are clear.

Anyhow, on June 11, this Labor Call wrote on another address given by Mr J. McKellar to the ALP’s Port Melbourne branch:

The lecturer prefaced his remarks by instancing the deep and lasting pleasure to be gained from the cultivation of the love of books. He spoke of the wonderful wealth of literature in the English language, and said that a feature of modern literature was that it got closer to the lives of the people.

He said writers like Bernard Shaw, H. G. Wells, and G. K. Chesterton “held the mirror of life by their works”, and recommended other works, including The Communist manifesto. But, reported the paper, he also said that

Too little appreciation was shown for our own Australian writers. One of the planks of the Australian Labor Party declared for the cultivation of an Australian sentiment. This was not, he stated, to be taken only in a political sense. The cultivation of an Australian sentiment was equally the work of Australia’s literary men.

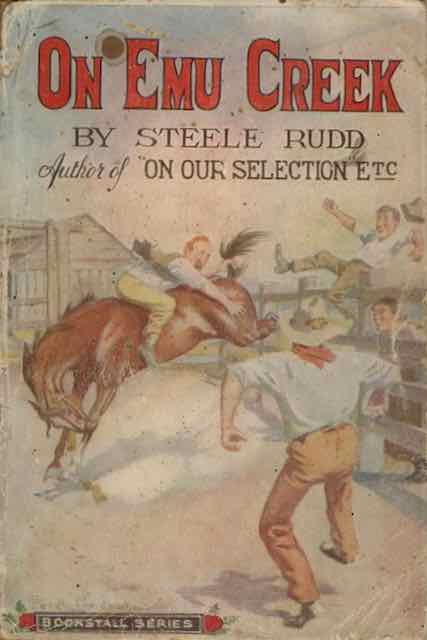

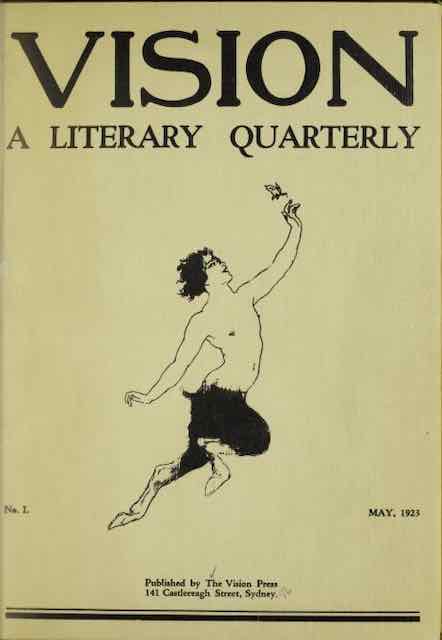

And he apparently named some who had done just this, including Fernlea Maurice (actually Furnley!), R. H. Long, and Vance Palmer. (R.H. Long does appear in the Australian Dictionary of Biography. It says he wrote “wrote topical verse, prompted to do homage to Nature and to denounce capitalism …”)

A few days later, on June 17, The Australian Worker reported on the same lecture. They also wrote of his comments on the lack of appreciation for Australian writers, and on the fact that one of the ALP’s planks was “the cultivation of an Australian sentiment”. They continued:

He might have added that, generally speaking, Australian writers have to go to London for an audience that will appreciate — and pay for — their songs and stories of the land that froze them out.

Ouch!

Australian literature and art in schools

Quite coincidentally, the topic of teaching Australian literature in schools that came up in my 1925 Trove research also came up, briefly, in comments on a #Six Degrees post this weekend – on host Kate’s (booksaremyfavouriteandbest) post, in fact. She linked to David Malouf’s Ransom because one of her children had studied it at school this year (as they had, the American starting book, Shirley Jackson’s We have always lived in the castle). Rose (RoseReadsNovels) chimed in saying her children had, in the past, read another Australian novel for school, Melina Marchetta’s Looking for Alibrandi. I remember being disappointed when my children were in Year 11 and 12 that there was little if any contemporary (or any) Australian literature in their curricula.

The inclusion of Australian books in school curricula was also mentioned, in passing, in a Canberra Writers Festival session I attended – Poems of Love and Rage – with both Evelyn Araluen and Maxine Beneba Clarke mentioning that their books, Dropbear (my review) and The hate race (my review), were taught in schools. I love that recent Australian books speaking to current lives and issues are being taught. I know it’s neither easy nor cheap for schools to teach recent books, but I believe it is important.

This is not, of course, a new issue. It was discussed in the newspapers in late 1925 – on December 17 in Sydney’s Evening News (briefly) and The Sydney Morning Herald, and on December 18 in Newcastle Morning Herald and Miners’ Advocate (not then part of the SMH group) – after members of the Australian Journalists’ Association (AJA) had met with Mr Mutch, the Minister for Education. They argued that “to foster a pure Australian sentiment” there needed to be “an increased study in the schools of Australian literature and art”.

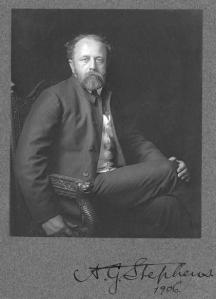

The best definition of “pure Australian sentiment” came from the critic A.G. Stephens, who, said the SMH, declared that “our literature was the mirror of our lives, and naturally we desired to see reflected in it our own country, lives, and characteristics.” He argued, wrote the SMH, that it was better “for children to read of gum-trees and their 400 varieties than of oak and fir trees” but that children were only learning “scraps of Australian literature, the lives, personalities, and ideals of the writers”.

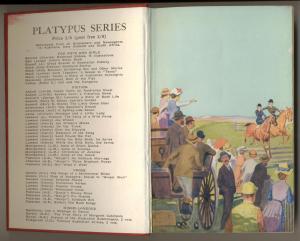

The AJA also said that “the Australian author and artist were not getting a fair show in their own country”. They wanted the Department to work towards a “proportion at least 50 per cent” of Australian works in the schools. The Minister, a political being of course, disagreed with some of their condemnation but generally agreed with their sentiment! However, he said that “The department suffered from a constant financial malnutrition, and the purchase of Australian books was restricted on this account”. (The NMH&MA described the money issue as “a chronic state of financial stringency”.) Then he offered them another tack. They could

also arrange with the grand council of the Parents and Citizens’ Association that at least half of the prizes purchased for distribution at the end of the year should be Australian-made.

Nothing like passing the buck! But, not a bad suggestion all the same. The Evening News had its own suggestion. It argued that “if Australian literature were used largely in the examination papers, it would be taught as a matter of course in all the schools” and suggested that rather than approach the Minister, the delegation approach the University! I presume examinations were set by the University at that time.

And so it goes … (to use my best Vonnegut).

Thoughts, anyone?