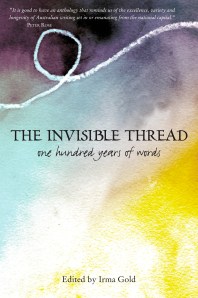

Bagging Canberra – often used synonymously for the Federal Government – is almost a national sport, but in recent years anthologies have appeared to counter this with more complex stories about this place. The first two I’ve read – The invisible thread, edited by Irma Gold (my review) and Meanjin’s The Canberra issue (my review) – commemorated Canberra’s centenary, but last year saw the publication of the evocatively titled These strange outcrops.

This anthology is the work of two young Canberrans, Nancy Jin and Rosalind Moran, who founded Cicerone Journal. Established in 2018, it is, they say,

a Canberra-based publication that seeks to encourage an open curiosity about the world in a socio-political climate of disconnection and disenchantment. We aim to publish writing that is exploratory and thoughtful, and new and unusual.

The journal’s fifth edition will be devoted to speculative fiction, and is due soon.

So now, These strange outcrops, which is subtitled, Writing and art from Canberra. It comprises original short stories, poems, and visual art created by established and emerging Canberra writers, and has a specific goal, as the editors write in their Foreword. It “grew out of a desire to question media narratives that portray Australia’s capital city as a place of disconnection and insularity”. They note that with a population of 400,000, Canberra and the surrounding region is “home to far more stories and perspectives than are commonly depicted in the news”. They wanted, they say, to “challenge the prejudices and stereotypes” and “celebrate the varied lives and imaginings of this unique place”.

“blurry at the edges” (Owen Bullock)

They have achieved their goal, and with style. This publication is physically gorgeous, from the cover, with its iconic Canberra bus stop framed by two Canberra floral emblems (the Royal Bluebell and Correa), through its beautiful endpapers comprising a correa blossom pattern, to the care taken with the design of the individual pieces. I can’t imagine any contributor not being thrilled with the look of their contribution.

But, the main point is, of course, the content. It more than lives up to the appearance, by which I mean, the book is not just a pretty face. An important thing with anthologies is the order, and it’s clear that the editors thought carefully about this. They start with the physical Canberra, and its natural environment, which is one of the reasons many of us love this place, and conclude with the experiences of different members of Canberra’s diverse population. In between, are various explorations of a wide range of aspects of life in Canberra, from those common to us all (like Cheryl Polonski’s poem “Wintertime in Canberra” and Penelope Layland’s poem “Showtime”) to some that speak to more specific experiences (like Daniel Ray’s prose piece about that challenging post-Year-12 time, “Queanbeyan: Quinbean: Clear water”). Some contributions are movingly personal, while others are unapologetically political. The end result is an authentic whole, that shows Canberra to be a rich and complex place, a bit “blurry at the edges” but with enough commonality at the core that makes us real, regardless of what outsiders might think.

Now, I did have some favourites, and will share a few of them over the rest of this post. The opening set of poems, “Canberra Haiku” by Owen Bullock beautifully introduces the collection, with its series of little impressions portaying Canberra’s breadth, from flowers peeking through a cracked pavement to a tattooed bus passenger and a permaculture working bee, from magpies and our mountains and lake to heatwaves and “blurry … edges”. The next few pieces explore place, often with an awareness of what was before we came, such as Janne D Graham’s poem “Crace Park” which conveys a sense of wrongness in our “calculated spaces”. A sort of antidote – or comment on this – is Helen Moran’s vibrant painting “Rainbow Serpent sleeping in Lake George”, the Rainbow Serpent being significant to many First Nations Australia peoples. It mesmerises me, because, while looking simple, it evokes complex and conflicting ideas. Set against a dark blue and black background, the bright, cheery serpent also looks ready to pounce. At least, that’s how it appears to me.

Some of the pieces invoke wry humour to make their point, like Fiona McIlroy’s poem “sky whale” which uses the Patricia Piccinini’s Canberra-Centenary-commissioned hot-air balloon “The Skywhale” to reflect on attitudes to public art that challenges perceptions.

Canberra is

determined

to have a whale of a time

in the Centenary

to live it up

to lighten up

kick up our heels

yet a flying

maternal mammal

is just pushing the

envelope

The wordplay throughout the poem is delicious.

“come so far, lost so much” (Joo-Inn Chew)

Some of the strongest pieces concern migration and racism. Canberra, like much of Australia, is a multicultural place. We have Ngunnawal and other First Nations people here; we have Australian-born residents who have come from around Australia for work; and we have migrants including refugees. We have – or had, before the pandemic – an annual, vibrant and successful Multicultural Festival, which celebrates this aspect of the region, but several pieces in the anthology convey the sadness and pain that must always come with migration, regardless of its cause. Anita Patel speaks in “What are you cooking?” of the sadness of losing her mother in another part of the world, so that even those weekly phone conversations are no longer possible, while Joo-Inn Chew’s poem “A new arrival at Companion House” talks of the hope contained in the birth of a baby to people who have “come so far, lost so much”.

Others are much darker, speaking to non-acceptance, such as Michelangelo Curtotti’s ironically titled poem “The welcome”. In one of those perfect segues, this poem is followed by Stuart McMillen’s graphic short story, “I used to be a racist”.

As frequently happens when reviewing anthologies, I’ve only cursorily dipped into the treasures contained within. I apologise to all those contributors whom I don’t mention here, but know that you’ve been read and heard. The best thing would be for more to read your work in this thoughtful, considered anthology. It can be purchased from Cicerone (linked above).

Meanwhile, let’s finish on Rafiqah Fattah’s defiant poem, “Generation selfie”, about the 16 to 25 year olds who are too often ignored or passed over:

And now, there is a tremor in the air

We are here

Nancy Jin and Rosalind Moran

These strange outcrops: Writing and art from Canberra

Canberra: Cicerone Journal, 2020

74pp.

ISBN: 9780646814155

The session was billed as follows: “Some of Canberra’s finest and most creative writers join forces in this irresistible ode to the national capital. Take a wild ride through a place as described by the vivid imaginations of some of this city’s best talents. Capital Culture brings stories not just of politics and power, but of ghosts and murder and mayhem, of humour and irreverence, and the rich underlying lode that makes Canberra such a fascinating city.”

The session was billed as follows: “Some of Canberra’s finest and most creative writers join forces in this irresistible ode to the national capital. Take a wild ride through a place as described by the vivid imaginations of some of this city’s best talents. Capital Culture brings stories not just of politics and power, but of ghosts and murder and mayhem, of humour and irreverence, and the rich underlying lode that makes Canberra such a fascinating city.”