The best way I can describe Christos Tsiolkas’ latest novel Barracuda is to liken it to what Tsiolkas would define as a “good man”, tough on the outside, but tender within. I don’t know how Tsiolkas does it, but he manages to reach into your heart while at the same time confronting you to your core.

On the surface, Barracuda is about success and failure, specifically in sport. The plot concerns Danny Kelly aka Psycho Kelly aka Barracuda who is a talented swimmer. He receives a scholarship to attend one of Melbourne’s elite private schools and be coached on the swim team. Danny, with his Scottish truck-driving father and Greek hair-dresser mother, is not the normal demographic for the school and feels an outsider from the start, but he knows – or believes, at least – that he can be “the strongest, the fastest, the best”. However, things don’t go according to plan and Danny, who had poured his all into a single vision for his future, is devastated. The novel explores how a young man copes with such a major blow to his self-image, what happens when his expectations for his future are destroyed. Tsiolkas examines the social, political and economic environment in which Danny lives and the role they play in what happens to him, but he also delves deeply into the psyche, because what happens to Danny can only be partly explained by external forces. In the end we are, as Danny comes to realise, responsible for ourselves and our actions.

Contemporary writers annoyed him

Barracuda is quite a page-turner, but it bears slow reading, because it is a carefully constructed novel and some of its joys come from considering what Tsiolkas is doing. There is an amusing moment in the book when Danny, now in jail, becomes an enthusiastic book reader – primarily of 19th century novels. When the librarian asks:

‘Why are you always buried in those old farts?’ Danny would accept the teasing good-naturedly for he knew it was apt. Contemporary writers annoyed him, he found their worlds insular, their style too self-conscious and ironic.

I say amusing because there’s a self-consciousness in Tsiolkas’ style and I can only assume that he is having a little dig at himself. The novel’s structure reminded me somewhat of Evie Wyld’s All the birds, singing (my review) because both start at a point in time and then, in alternating chapters (sections), radiate forwards and backwards from that point. Tsiolkas, though, follows this structure a little less rigorously than Wyld, and he combines it with a change in person. In the first half of the novel, the sections moving backward are told in third person (limited) through the eyes of Danny, while the sections moving forward are told in first person through the eyes of Dan. This effectively enables the growing, maturing Dan to disassociate himself somewhat from his old self, although the dissociation – or perhaps the reintegration – of the two selves have a long way to go when the book opens. In the second part of the novel the point-of-view is reversed with the third person used for the older Dan, and first person for the younger, perhaps suggesting some progress towards the realignment of the selves? I need to think about this a bit more! Not only does this book warrant slow-reading, but rereading wouldn’t hurt either.

He couldn’t bridge the in-between

A significant issue for Dan is managing the two worlds he finds himself in:

It’s like two worlds were part of different jigsaw puzzles. At first, he’d tried to fit the pieces together but he just couldn’t do it, it was impossible. So he kept them separate: some pieces belonged to this side of the river, to the wide tree-lined boulevards and avenues of Toorak and Armadale, and some belonged to the flat uniform suburbs in which he lived.

When the two worlds conflict, Danny feels split open, cracked apart. “No one could ever put him back together”. And so, he starts to occupy what he calls “the in-between” but that leaves him silent, and alone. This dissection of worlds, of “class”, and of anglo-Australia versus immigrant Australia, is an ongoing concern for Tsiolkas. We came across it in his previous novel, The slap (my review) and we see it again here. Tsiolkas is not the only writer exploring this territory, but he’s one of the gutsiest because he’s not afraid to present the ugliness nor does he ignore the greys, the murky areas where “truth” is sometimes hard to find (though he doesn’t use the word “truth”).

While Danny is the main conduit for teasing out the tensions in society between two worlds, other characters also reflect it. There’s Danny’s childhood friend, Demet, whose working class migrant background is challenged when she goes to university, and his school friend Luke, a nerdy ostracised boy at the elite school who, with his Vietnamese mother and Greek father, is also “half and half”. These characters manage to traverse their worlds more easily than Danny, but Tsiolkas shows that it isn’t easy.

His father was a good man

Barracuda is about a lot of things. It’s not an exaggeration to say that Tsiolkas taps into the zeitgeist of contemporary suburban Australia. But I might explore that in another post, because this post is getting long and I do want to end on the theme that struck me the most, that of defining “a good man”.

Throughout the novel, Danny meets many men – his father, grandfather and coach, in particular, when he’s a boy, and his lover Clyde, old schoolmate Luke and brain-damaged cousin Dennis when he’s an adult. As an adolescent, and somewhat typically, Danny loves his grandfather, rejects his father, and dotes (until he “fails”) on his Coach. Adult Dan is more circumspect about men, but sees good qualities in Clyde and Luke, while still rejecting his father. None of these men, though, seem able to break through his destructive self-absorption. However, late in the novel, living a self-imposed lonely life, albeit one now committed to helping others, Dan has an epiphany. In a confrontation with his father, he suddenly realises:

His father was a good man. It struck him with a force of revelation, exultation, light flooding through him. His father was a good man. His father was the hero of his own life.

At this moment, he realises he wants to be a good man. He also starts to get a glimmer of what a good man is, and it has nothing to do with being the strongest, fastest and best.

I have more to say about this book, and so will do a follow-up post rather than write a longer essay here. Meanwhile, I know there are readers of this blog who do not like Tsiolkas. He is, I agree, a confronting writer. His characters are not aways easy to like, and he doesn’t shy away from their grubbiest (that is, unkind, violent, sexual) thoughts, but for me he has some valid concerns to share and I want to hear them.

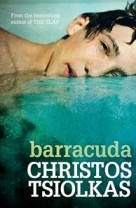

Christos Tsiolkas

Barracuda

Sydney: Allen & Unwin, 2013

515pp.

ISBN: 9781743317310

Oh, this sounds like a wonderfully complex and juicy novel! That bit of poking fun at the style of contemporary novelists is pretty good. I very much enjoyed reading your review, especially the last part about the discovery his father was a good man.

Thanks Stefanie … Juicy is a good word, which is why I’m currently drafting another post!

I’m skipping this review because I think it’s high time I actually read Tsiolkas… and spoilers! (I don’t know if there are spoilers, but better to be safe than sorry.) I’d ask you to bring on of his novels to Canada, but you might not get it back before you leave?!

And it’s a BIG heavy novel. I don’t aim to do spoilers but I don’t read reviews before I read books just because I don’t want to read someone else’s impressions first.

I really enjoyed Barracuda. I did find the anger and self-obsessiveness in the novel a little hard to handle but as far as I’m concerned that only added to the novel. I don’t think you have to like the main characters to like a book.

Totally agree sharkell … The novel is confronting in those aspects but as you say that’s part of its power.

An insightful review of a really good book.

Thanks bushmaid – I enjoyed writing this review. Funny how some are easier to write than others!

I’m looking forward to reading this. It looks like an interesting and challenging journey. I did enjoy The Slap – it’s harshness sort of spurred you on. Often so unappealing but always compelling. I think this could also do with a reread!

Yes, I agree, Catherine, he’s confronting, offensive at times or vulgar as I heard someone else say, but you want to keep reading because the characters are always interesting. I listened, yesterday, to an interview with him in which he said that he’s sorry that Sandi (the abused wife of Harry) didn’t have a voice in The slap. I’m not sure but I got the impression that she (or a character like her) may be the inspiration for his next book. I guess time will tell.

Yes I think he could easily develop Sandi. He’s a great, very human, speaker too – I heard his Ubud interview last year.

Thanks Catherine … You are right about him as a speaker. Very human and very honest I think.

Hi Sue, this is such a wonderfully thoughtful review. I especially enjoyed this: ‘Tsiolkas is one of the gutsiest [writers] because he’s not afraid to present the ugliness nor does he ignore the greys, the murky areas where “truth” is sometimes hard to find (though he doesn’t use the word “truth”). Tsiolkas certainly doesn’t shy away from ugliness (I’ve read all his novels) but I’m always surprised to hear that some readers find that ugliness, or the force of that ugliness, too much. There’s always tenderness in this novelist’s work, and that tenderness is prominent in ‘Barracuda’. He’s also unafraid to shine a very strong – yes, sometimes harsh – light on why Australia may not be the best country after all; he’s very aware of this country’s strengths, but he also likes to reveal where we are weak and/or repugnant. One of the things for me that I liked about ‘Barracuda’ over his other works is its international focus coupled with his brutal dissection of Australian sport. Thanks for getting me to think about these things through the writing of your review!

Thanks Nigel … Yesterday I listened to a conversation with Tsiolka at Ubud a year or so ago. He said that the main critics of his work tend to be Anglo-Celtic women. He also suggested that as this group also forms the biggest reading public that writers tailor their work a little to its sensibility. I liked his fearlessness in saying that. As an Anglo-Celtic woman I do find him confronting at times but I like to be confronted – in the arts.

And yes, his critique of Australia here is good -something to get our teeth into. I’m drafting another post now and plan to talk a little about that.

I’d been wondering about this novel, but your review has convinced me it’s worth a read. I do like juicy and confronting, but throughout The Slap and another book of his (I can’t quite recall it, even though I own it…) it felt a little forced. I’ll be interested to see if it’s approached differently.

That’s interesting Tara (I assume that’s your name?). I didn’t find The slap forced, though I suppose it did have a very particular structure. I haven’t read his earlier works though would like to find time to. I felt that Barracuda was tighter and more focused than The slap (which I liked a lot but felt it lost itself a little towards the end). I’d love to know whether you thought the same.

Ah… I’ve done my googling and the book I’m referring to is Loaded, which I think was his first novel. I *completely* agree with you re The Slap. The character development and descriptions pulled me in in such a big way, and I remember discarding both the TV show *and* the book before the final ‘chapters’. It held a lot of promise and depth and (if I recall correctly) lost its way a little with the full development of Connie. But I enjoyed the descriptions so much that I bought Loaded, but then felt disappointed (a different storyline but felt repetitive with The Slap in terms of feeling purposefully confronting – and yes, very confronting for 1995, but I felt Jenny Pausacker was doing better, deeper work in that era). I’ve downloaded the sample of Barracuda and I’m sure I’ll read the novel – I will let you know!

And yes, my name’s Tara 🙂

Thanks Tara! Yes, Loaded was his first, and was made into the movie Head On, but I haven’t read it or seen it. I’ve heard of Jenny Pausacker but haven’t read her. Will look her up.

Tsiolkas *is* purposefully confronting. It is part of what he wants to do I’ve learnt – to make us uncomfortable, makes us see lives that may not be known to us but that are part of contemporary Australia. He wants us to question our assumptions. (Over the last week, I’ve listened to and read some interviews!)

I’ve no doubt… It’s his whether he does it forcefully or somewhat contrived which I struggle with. I read ‘Getting Somewhere’ by Pausacker as a pre-teen and found it confronting but relatable. I wonder if I would have found Tsiolkas’ work the same? I will report back on Barracuda – you have inspired me in a huge way and made me really think through my opinions. Love it!

Why are you still up? I’m retired so I’m allowed to be! I’m thrilled to have inspired you – that’s the best thing a blogger can hear isn’t it? I look forward to your comments when you manage to read any, but I do know how busy life can get.

Hi Sue, Just catching up on all my blog reading! I expect I’ll pick this book up at some stage but it’s not high on my list, as I’m a bit turned off by the sloppiness of his writing and character portrayal (which I found 2-dimensional in The Slap). However he *is* one of the few writers addressing suburban themes in Oz, which is laudable.

And just catching up on my past comments! You are right about his being one of the few addressing suburban themes … I’m planning to write about that in the near future. He seems to be a writer people either love or hate. I don’t find his writing sloppy – though can see why some might I think.

I’ve been thinking about your charge of two-dimensionality. I don’t think I found it that way. While I can see some characters could be seen that way, I felt they were pretty real in their two-dimensionality, if that makes any sense at all. In other words, you sense that they’re might have been more to them but in terms of their relationships with other characters in the book they made sense and were realistic. In other words, we only saw the dimension that was relevant to their role in the book in the way that some people see one main dimension of me while others see another, while still others may see several of my dimensions. Does that make sense? Thanks, anyhow, for making me think about why his characterisation didn’t bother me!

I said in my reading group that I thought Barracuda was tighter and more focused than The slap. I’m not sure all the characters are more “dimensioned” but I think the main character is pretty complex, at least in the sense that he grows in self-understanding.

Thanks for this thoughtful review. The more I hear about this book the more I think I should read it. Two major Australian writers (Tsiolkas and Winton are coming to my city – Calgary – for our major book festival this fall) and I am hoping to attend a number of events.

Oh Rough Ghosts, that’s wonderful to hear. They are both excellent speakers so are worth getting to if you can.

Both are scheduled for one hour one-to-one interviews. I am making my wish list now, I think there are at least four authors I want to see in this format (including a Canadian, Michael Crummey and the Icelandic author Sjon). Being on sick leave right now I can get involved for the first time. In the job I was working October is too insanely busy.

Have you a suggestion for where to start with Tim Winton. I imagine he will focus on his latest but I wonder where you would start to get a taste for his work?

His most famous is Cloudstreet. It is often voted in the top 10 of Australian novels – both by readers and writers themselves. It’s a great read. The turning is sort of interconnected short stories – and was recently made into a very unusual long long film.(Google it to see what I mean). I like it a lot too. I thought Breath was stunning. It’s short and some really don’t like it, but I found it a powerful study of risktaking in boys/men. Dirt Music has mixed reactions … a good and typical read, but many of us felt the ending lost it a bit, became a little melodramatic. Some of his early novellas are well worth reading too, That eye the sky and In the winter dark. Any of these would be great introductions I think. I missed Eyrie, his latest, when my reading group did it – was overseas – so still have to catch up on it.

Thanks, sounds like there is a lot to choose from, I may go for length given my endless TBR list, just to get a taste. 🙂

I think that’s a very reasonable compromise! Breath is short – as well as those two novellas I named. You could also look at his straight short story collections, like Scission, though some will be hard to find now I guess.

Pingback: Barracuda by Christos Tsiolkas | His Futile Preoccupations or The Years of Reading Aimlessly.....

Hi whisperinggums. As a follow up to our chat here last month I have yet to see Tim Winton tomorrow but I loved Barracuda and had the absolute pleasure to meet and talk with Chistos at length after his presentation today. He was animated and delightful in the interview but supportive of my challenges with some writing I am trying to do in a way that was above and beyond what I could have imagined.

That’s wonderful Rough Ghosts. I haven’t seen him in person but the interviews I’ve heard have impressed me, and people I know who have met him say he is a lovely, gentle man so I’m not surprised by what you say. So glad you enjoyed the book.

I loved this book, as painful as it was to read sometimes. A wonderful review!

Oh, thanks so much Marg for commenting. It’s great when someone loves a book and my review, And welcome here.